A spacecraft that died in 2017 is still providing insights about Saturn, the planet it studied up close for 13 years.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft helped scientists to discover why Saturn's upper atmosphere is so hot, which puzzled planetary scientists for decades since the planet is too far from the sun to receive our star's heat. But, using old data from Cassini, scientists are closer to solving this mystery.

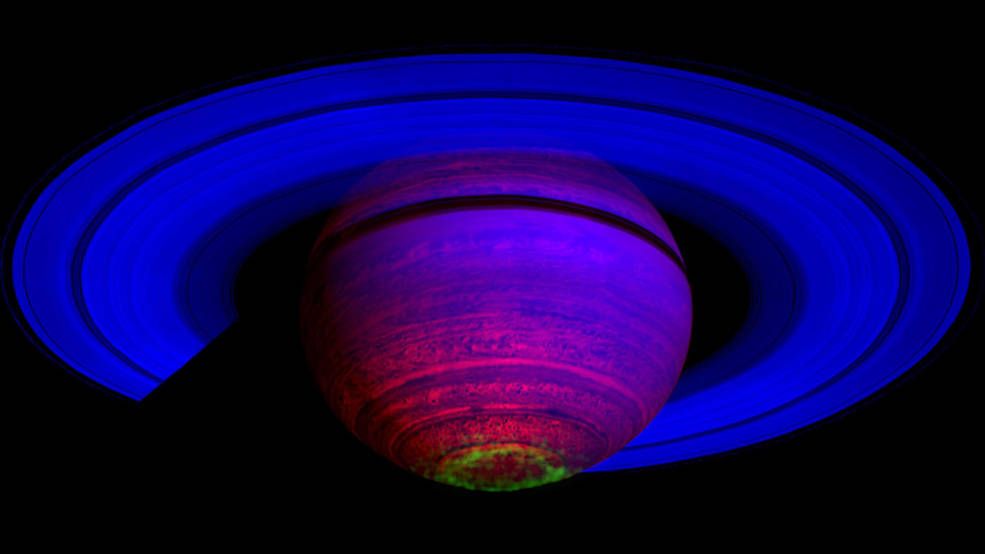

This new work, which was conducted by NASA and the European Space Agency and led by Zarah Brown, a graduate student at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, suggests that it's auroras that are heating up Saturn's atmosphere. These auroras are triggered by the constant stream of charged particles from the solar wind, which interacts with charged particles that flow from Saturn's moons and creates electric currents.

This insight not only helps scientists understand what is going on at Saturn, but perhaps also at gas giant planets in general. Jupiter, Neptune and Uranus all have strangely hot upper atmospheres as well. There are also numerous exoplanet gas giants far outside of our solar system that may exhibit similar behavior.

"The results are vital to our general understanding of planetary upper atmospheres, and are an important part of Cassini's legacy," study co-author Tommi Koskinen, a member of Cassini's Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph instrument team, said in a statement from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Researchers previously used Cassini data to build a map of the temperature and density of Saturn's upper atmosphere, which was not well known before the spacecraft arrived at the planet in 2004. In this study, this map helped scientists to study how electric currents from Saturn's auroras heats the planet's upper atmosphere, generating the solar wind. The solar wind, in turn, distributes energy from the poles (where the auroras are located) towards the equator. That energy then heats the equator to twice the temperatures than could be generated from the sun's heat.

It's common for archival data from spacecraft like Cassini to continue providing new insights long after the craft are no longer operational. This particular dataset came from Cassini's final few months at Saturn when it did 22 very close orbits of the gas giant before deliberately hurling itself into the planet on Sept. 15, 2017 (to prevent possible Earthly contamination of Saturn's icy moons, which could host microbial life.)

For six weeks, Cassini examined bright stars in the constellations Orion and Canis Major, watching as the stars rose and set behind Saturn. By observing the shifting starlight, scientists were able to learn more about the density of Saturn's atmosphere. Since density decreases with altitude, the rate of decrease is dependent on temperature, allowing scientists to estimate temperatures in Saturn's upper atmosphere.

Cassini's observations showed the temperatures peaking around the auroras, in turn providing evidence that it is electric currents are what Saturn's upper atmosphere so hot. Wind speeds on Saturn were also determined using density and temperature measurements.